Jane Austen at 250: The Most Radical Woman in the Room

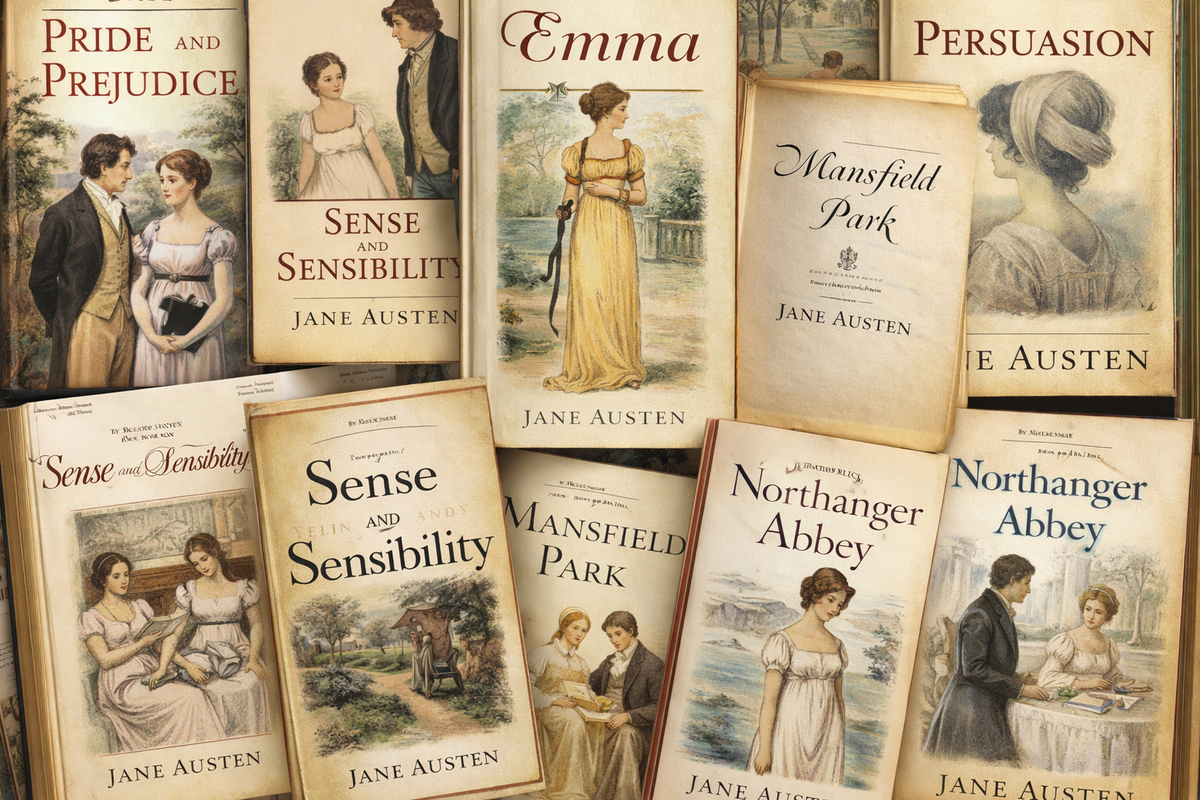

Celebrating the 250th birthday of Jane Austen, a woman often mischaracterized as a writer of polite romances and drawing-room manners. That misconception does her a profound injustice. In her own time—and especially given her circumstances—Jane Austen was nothing short of revolutionary.

Born in 1775, Austen lived in an era when women had no political voice, no legal independence, and almost no economic autonomy. Marriage was not simply a romantic aspiration; it was survival. Property passed through male lines. Women could not easily earn money, inherit estates, or control their own futures. Against this rigid backdrop, Austen dared to write novels that quietly—but relentlessly—questioned the entire system.

Her revolution was not fought with speeches or pamphlets. It was waged through wit, irony, and precision. Austen exposed how marriage, supposedly a romantic ideal, was often an economic transaction that left women vulnerable and constrained. In Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, Emma, and Persuasion, she centered women’s interior lives—their reasoning, judgments, moral growth, and emotional intelligence—at a time when women were widely assumed to be intellectually inferior.

Elizabeth Bennet’s refusal to marry without respect and affection was a radical act. Anne Elliot’s quiet endurance and later reclamation of agency defied the notion that women’s value diminished with age. Even Emma Woodhouse, wealthy and flawed, is allowed something rare for a woman in 1815: the right to be wrong, learn, and grow. Austen granted her female characters moral authority over their own lives, not because they were perfect, but because they were human.

Equally revolutionary was Austen’s satirical dismantling of male entitlement. Her novels are filled with pompous clergymen, idle aristocrats, predatory charmers, and fragile egos—all exposed with surgical humor. She did not shout; she skewered. In doing so, she inverted the power dynamic of her world. The men may have held the land and the law, but Austen gave women the sharper minds.

Perhaps most subversive of all was her authorship itself. Writing was not considered a respectable profession for women. Austen published anonymously, yet she wrote with absolute confidence in her craft. Her prose was economical, exacting, and intellectually demanding. She trusted her readers to understand irony, recognize hypocrisy, and detect injustice without being instructed how to feel. That trust alone was radical.

Jane Austen also rejected melodrama and moral preaching—common tools of her time—in favor of realism. She portrayed women not as angels or cautionary tales, but as thinking individuals navigating unjust systems with resilience, humor, and quiet rebellion. In a society that prized female silence, she made women observant. In a world that demanded compliance, she made them discerning.

Two hundred and fifty years later, Austen endures not because she wrote love stories, but because she wrote freedom into constrained lives. Her revolution was subtle, but it was devastatingly effective. She taught generations of readers—especially women—that clarity of thought, self-respect, and moral courage are forms of power.

That is why Jane Austen remains revolutionary still.

In the spirit of Jane Austen I’m participating in a special protest today. Getting in Good Trouble.

Julie Bolejack, MBA

The Mindful Activist

Subscribe at julies-journal.ghost.io