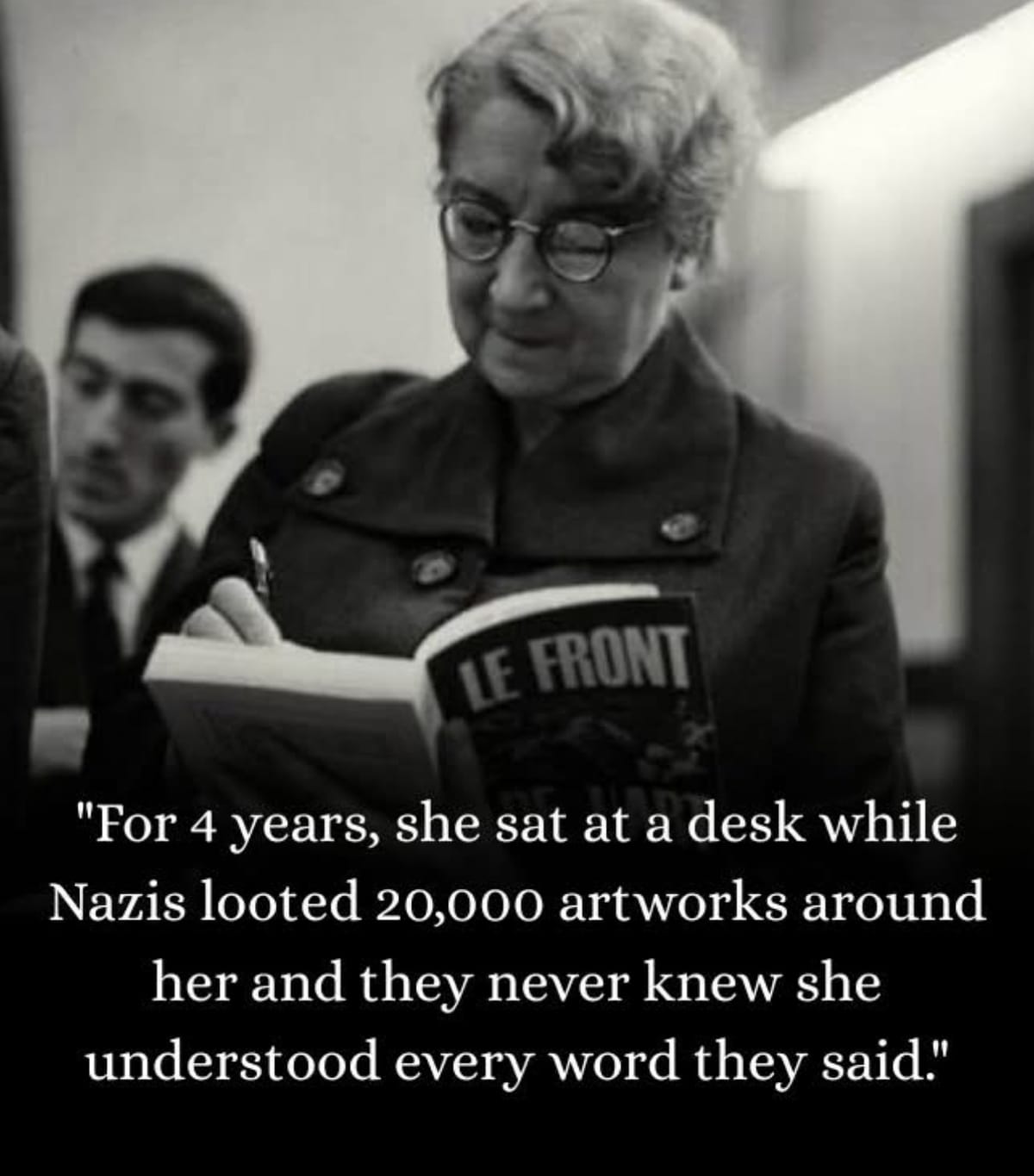

They Thought She Was Nobody. History Proved Them Wrong.

Saw this story on Facebook and it fascinated me...sharing:

For four years, a woman sat at a desk while Nazis stole 20,000 works of art.

They thought she was furniture.

Paris, October 1940. The Nazis had just taken over the Jeu de Paume museum and turned it into their personal Amazon warehouse for stolen culture. This is where art looted from Jewish families was brought, sorted, admired, and shipped off to Germany like luxury souvenirs from a genocide.

And sitting quietly at a desk inside this operation was a woman named Rose Valland.

To the Nazis, she was nothing. A clerk. A mouse. Background noise. The kind of woman men like Göring literally do not see.

Which, as it turns out, was their first really expensive mistake.

Rose was 42. She was an unpaid volunteer curator. She had degrees from the École du Louvre and the Sorbonne. And when the Nazis arrived, the director of France’s museums gave her what was essentially a suicide mission:

Stay. Watch. Remember everything. Write it all down.

Most people would have run. Rose stayed.

Every day she watched crates come in — entire lives packed into wooden boxes. Vermeer. Monet. Cézanne. Renoir. Collections built over generations, ripped out of Jewish homes under the polite fiction of “protection.” (The Nazis were very big on theft with paperwork.)

Hermann Göring himself showed up twenty-one times to shop for art like a man picking out throw pillows for his castle. Rose was always there. Silent. Invisible. Taking notes in her head.

And here’s the part that still makes me smile grimly:

They never realized she spoke fluent German.

For four years, not one slip. Not one raised eyebrow. She listened to everything. Train numbers. Destinations. Which masterpieces were going where. Every night she wrote it all down in secret notebooks, knowing full well that if anyone found them, she wouldn’t get a trial. She’d get a wall.

She also passed information to the French Resistance so they wouldn’t accidentally blow up trains full of France’s stolen cultural soul during sabotage missions. (Imagine having to choose which trains deserve to survive. History is a monster.)

In July 1943, the Nazis decided to have a little bonfire. Five hundred paintings — Picasso, Miró, Klee — were declared “degenerate” and burned in a pile on the terrace.

Rose watched from inside.

There are moments in history when all you can do is witness and remember. This was one of them.

By August 1944, as the Allies were closing in, the Nazis panicked — the way thieves always do when they hear footsteps. On August 1, Rose discovered that 148 crates of Cézanne, Monet, and Renoir had been loaded onto a train headed for Austria.

She had the railcar numbers.

She sent them to the Resistance.

The train never made it out of France.

When Paris was liberated, Rose was promptly arrested — because of course she was. A woman who stayed at her post during the occupation must be a collaborator, right?

Only later did they realize who she really was.

What she produced stunned everyone: meticulous records of more than 20,000 artworks. Shipping manifests. Routes. Storage sites. A paper trail so thorough it might as well have been a map with skulls and arrows on it.

She joined the French First Army as a lieutenant and went to Germany with the Monuments Men. For eight years. Eight. Not for glory. Not for headlines. For receipts.

Her work led them to Neuschwanstein Castle, stuffed with over 20,000 stolen works. Then to mines. Bunkers. Castles. She even tracked down Nazi officers she’d quietly observed for years and interviewed them like a librarian with a long memory and absolutely no patience.

In 1946, she stood at Nuremberg and confronted Hermann Göring.

The man who had shopped for art in front of her for years was finally forced to answer to the woman he never bothered to notice.

By the time it was over, Rose Valland had helped recover about 60,000 artworks. Forty-five thousand went back to their rightful owners — many to families who had lost literally everything else.

Captain James Rorimer of the Monuments Men later said:

“The one person who above all others enabled us to track down Nazi art looters was Mademoiselle Rose Valland.”

She became one of the most decorated women in French history.

And then she went back to work.

No brand deals. No speaking tour. No “inspirational memoir” circuit.

Just a woman who understood that memory is a form of resistance.

Rose Valland never fired a gun. Never blew up a bridge. Never hid refugees in an attic.

She did something quieter. And just as dangerous.

She wrote things down.

And because she did, tens of thousands of stolen lives — their beauty, their history, their proof of existence — were not erased.

For four years, she sat at a desk, moving a pen across paper, while monsters talked around her in a language they thought she didn’t understand.

Her greatest weapon was being underestimated.

Which, as history keeps proving, is a very bad idea.

History doesn’t always announce its villains. And it almost never announces its heroes. That’s why paying attention is a civic duty.

Julie Bolejack, MBA

I’m headed to Europe again this Spring. I hope to see some of the artwork she saved.

Subscribe at julies-journal.ghost.io to keep ahead of the censors and overlords. 🙏